So this week is another Narrative Justice week. This time it’s not on a totally obscure game that very few people…oh wait. Don’t forget to tell me what you think of this feature, and whether or not I should keep doing it in the comments or the thread for it in the forums. On that note, you should join the forums too.

But back on track, this week I’m looking at Comix Zone. I’m not going to talk about the narrative of this game because it’s not really that great: dude gets sucked into a comic book when it gets hit by lightning. Instead, I’m going to talk about the unique way that this game is told. It’s actually more of an art style thing, but Art Style Justice doesn’t sound as good as the current title. So click the “more” button and read up on it, sucka.

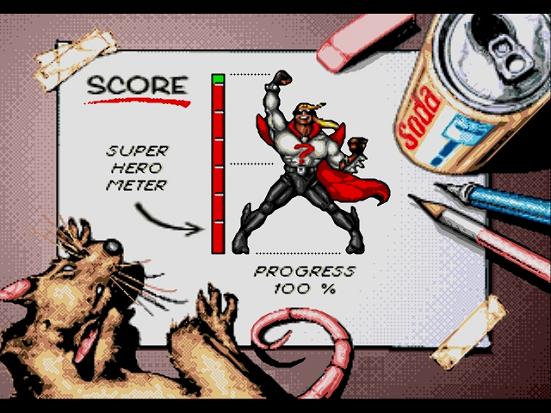

The comic book mechanic of the game is what makes it so interesting; this game mixes the narrative and visual styles of video games and comic books. In fact that overall art style probably does more good for the game than you might notice at first glance. The game is ridiculously difficult: enemies take forever to die, bosses are ridiculously hard, and it hurts you to break through barriers that you need to break through to advance. I mean, come on, it hurts you to do things you need to do. Imagine if in Sonic you lost a life every time you freed the flickies after beating Robotnik. Despite this, Comix Zone is a cult classic and is widely regarded as a great game. What’s the first thing everyone who refers Comix Zone to someone else says? “It’s so cool, man, it’s like you’re playing in a comic book.”

The game’s setting is actually a comic book that you’ve been sucked into, because it was hit by lightning (SCIENCE!). At the same time, the antagonist from the book has been sucked out of the book and can now interact with you as you progress through the story. He can now interact with you by drawing things into the comic, like villains and traps, and apparently he burns part of the page later in the game, but good luck making it that far. Good luck making it through the second part of the first act. Regardless of the game’s difficulty, it really is exciting to feel like you’re actually playing in a comic book. I’ve been playing this game off and on for over a year, and every time I play the unique setting still amazes me.

The game features very little conventional storytelling. There aren’t really cut scenes, and there’s very little dialogue. Instead there are the stereotypical yellow textboxes at the top of the panel that provide a small indication as to where you are. The storytelling itself is largely implied. Think of when you read a comic book and you see panels that are all action and no text. These panels still advance the plot and contribute to the story, and likewise every time you defeat a bad guy or solve a puzzle you’re contributing to the plot of the game. While the overall plot is always the same, it’s possible to build a unique story depending on how you play the game. For example, on the second page of the first chapter if you didn’t know that your rat can turn off the fans you would sustain more damage and the eventual boss fight would be more challenging to you. Conversely, if you had your rat and dynamite, you could sustain no damage at all and be in perfect condition when you reach the boss. Depending on how that scene turns out, the entire context of the boss fight could be changed. This is true in many games, but because of the comic book nature of Comix Zone, it’s much more apparent.

In this way your actions are actually important and have side effects in the story. That level of interactivity is what games like Mass Effect, Heavy Rain and Alpha Protocol promised, but failed to deliver on. Now obviously Comix Zone doesn’t provide that same kind of theoretical game-changing effects as those games, but it does provide several different contexts for the events in the game. Thinking back to my first example, if this game were drawn like a comic book (a comic book about a game about being in a comic book, that’s so meta) Sketch would be drawn damaged and bloodied going into the battle and there would be an air of panic and desperation. In the second example he would be depicted as much stronger and more confident in himself. In both cases it’s the same story line, but the context of the situation, and the way the battle will play out are completely different.

Obviously to get the full effect it takes some imagination, but the game being juxtaposed onto a comic book does much of the work for you. This setting sets Comix Zone apart from nearly all other games and makes playing it feel like a unique experience. No other game provides the experience that Comix Zone does, and very few tell a story in the same way. Sure, most beat-em-ups involve very little storytelling and just throw you into hoards of enemies, but in Comix Zone those battles play a part in the bigger picture of the story, even if it takes a little more thought than the average game to realize it’s there.