Deep inside a building in Oota, Tokyo, sits Sega’s ‘Room of Forlorn Hope’. Within resides a wheel-of-fortune and every few million or so hits on Sega’s websites earns a spin. Sometime in late 2012 just such a milestone was reached, the arrow of destiny flicked past Yakuza 5, ignored Border Break and showed indifference to Shining Force Cross Raid. Instead, Project DIVA F was selected and duly packaged off for translation to Western markets. Yet, all the fan-fare of finally receiving a Vocaloid title in the West ignores Miku’s presence on iOS devices, a presence that yielded two entries in the Flick series in 2012 alone. How rich a reflexion of the Vocaloid eco-system of games, music and video creation does Flick give now that the full-fledged titles are so freely available?

The Western localization of Project DIVA F gives Sega’s pop-bot a problem. Each game has to be all things to all fans, with players new to the Project DIVA series having come from Flick, Miku virgins whose interest has been piqued by the newly localized title, and yet more who are veterans of Miku’s iOS exploits without previously importing the PS3 or PSP games.

Despite Miku’s first home on Sony’s PSP, the Flick series possesses gameplay hugely removed from her high profile arcade, home and portable releases. Project DIVA broke new ground in its presentation, discarding the laser-focus on a strip of pixels where prompts would appear, Guitar Hero style, and adopting a pseudo-3D approach. Here, the background plane hosts the music video, rendered in real-time, whilst the prompts and inputs appear anywhere in the foreground plane. This utilizes the entire screen for the player whilst also creating an element of comedy and interaction between the two layers. Prompts chivalrously rescue Miku’s digital dignity when the camera veers dangerously close to fan service and both the player and voyeur alike is kept entertained in different, yet complementary manners. This structure stands testament to Sega’s expertise in Japan’s spectator friendly arcades.

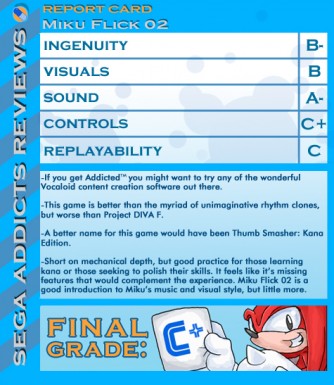

Miku Flick 02 in action. The base sound can be selected with just a press, as shown on the left. Other sounds need to be flicked out, right.

Strangely, Flick owes little of its gameplay to this heritage and prefers to use the template of a popular Japanese phone game. This game relies on a standard Japanese key pad where each button represents a base sound (‘ka/か’ for example) and flicks in the four directions select its derivatives (‘ki/き’, ‘ke/け’ ‘ku/く’ and ‘ko/こ’). The competitive element comes from swiftly hammering out the given sentence with wanton arthritic disregard. This template was used in the original Miku Flick, however, rather than simply pound through song lyrics as fast as carpal tunnel syndrome allows, inputs must be timed to the song lyrics. This is perhaps the greatest innovation in gameplay over Flick’s phone game forefather. The first Flick title changed the screen layout as well as the game mechanics. The screen was split in two, the viewing area for the pre-rendered music video occupies the top half with the translucent keypad on the bottom, a thin strip carrying the prompts bisects the two areas and never the twain shall meet.

This is a far cry from Project DIVA’s demands to parse the whole screen, a dislocation further emphasized as player inputs, due to the title’s heritage, rely upon the vocals rather than the beat. As titanically popular as this is in Japan, it can be an Herculean struggle with an unfamiliar language and a keypad lacking the cultural agnosticism of Sony’s buttons. Miku Flick 02 does little to change this formula, preferring instead to deliver ‘more’, rather than ‘better’. Nevertheless, the core gameplay of the Miku Flick games, tried and tested in Japan for some time, is well suited to its platform. The ‘short sharp shock’ demanded by mobile gaming is present here, indeed, a rhythm title is perfect given the way travel and music go hand in glove. Whilst those unfamiliar with Japanese kana will find a huge hurdle in playing the game at higher levels, the difficulty curve is actually well pitched with some longevity for those willing to put the hours in given the challenging hardest level.

Project DIVA F (PS3), quite the departure from Flick. Miku is no doubt thankful for the face-saving prompts here. She must get cold in that skirt.

Unfortunately, the whole package feels limited in scope and depth. New mechanics aren’t introduced as the difficulty levels are ascended, the limited number of songs (with more available as DLC, for a price, naturally) will lose their lustre, while the less than ambitious spectacle of the videos all debase what could have been an entertaining, well-rounded title. Even features which complement the social aspects of ‘phone gaming, the meta-game of Miku customization and her Vocaloid Room, are excised from the Flick series. This leaves a lightweight package that fails to represent the depth of the Vocaloid world, from fan composed songs through Yamaha and Crypton’s original program, to the bedroom coded videos that lend Miku and friends an element of design by democracy.

An able introduction to Miku’s sound and visual style the Flick series may be, but like chicory few will savour it when the full-bodied experience is so widely available. Both Flick titles do little more than scratch a teal-tinted itch when the player is separated from the arcade or console experience. In its attempt to ride a peculiarly Japanese zeitgeist, Western gamers will find both Flick titles to be little more than a gateway drug consumed in advance of Project DIVA F’s far more satisfying neon heroin.