General Chaos was one of the Mega Drive’s finest four player achievements. At once chaotic and sublime, cruel and comedic, it would have split families and friendships apart if it was not so much damn fun to play. The great news is that Game Refuge, the game’s creators, are still going strong and have turned to Kickstarter to bring the series up-to-date. General Chaos’ design genius did not emerge from a vacuum, but as a result of a distinguished body of work spanning back to the days when Atari ruled the nascent industry. With days left before the Kickstarter deadline, Brian Colin, CEO of Game Refuge, took some time out of his busy schedule to sit down with us to discuss his career and plans for his newest title.

Sega Addicts: You made award-winning short films in the late 1970s. How did you transition from film-making to the games industry?

Brian Colin: I was a young live action filmmaker who transitioned to animation after high school when I realized that cartoons were easier to control than live actors. Leaving college, I thought I wanted to be a classic, cel-painting animator until I was offered an entry level position at a New York Animation Studio; the 4-hour speed test was the most mind-numbingly boring four hours of my life.

Right around that time, I answered a help-wanted ad from the Bally Midway Company. I thought, “What would a pinball company want with an animator?” and decided that they needed someone with cel painting skills to create Marquee Glass art. I was wrong. Turned out they were interested in hiring me to create video game art and animation which, at that time, was not terribly exciting since everything was still pretty much in its infancy. I actually got a little sad when they made me a job offer because I thought, “…This is it; childhood’s over… I’ve got a Real Job”. Wrong on both counts. Game design turned out to be nothing like a ”Real Job,” and my childhood continues in full force to this day!

SA: Whenever I imagine game development in the 70s and 80s, I imagine Atari’s famous hedonism. How did Midway’s culture compare?

BC: I joined Bally/Midway in 1982 and was immediately impressed by the tremendous amount of peer-to-peer encouragement and support. This was a “Team” in the truest sense of the word. Bally/Midway’s In-House Development began in a small, overcrowded office on Hart Street in Franklin Park, Illinois. The original group was “offsite” (not physically part of the Bally/Midway factory) and that probably contributed to the close-knit, we’re-all-in-this-together feeling. Everyone helped everyone else, everyone pitched in, everyone was encouraged to contribute as much or as little as they wanted to. No egos, no politics, just a group of friendly creative folks who realized instinctively that having fun is a necessary part of the game development process.

We’d have countless impromptu field trips to nearby forest preserves, parks, museums and arcades that would invariably involve hours of great food, cold beer and raucous laughter… but we would routinely work 10-12 hour days, too. (I had a cot in the corner of my cubicle that I’d use at least once a week.) Management left us alone for the most part. I think they thought of us as an unusual, albeit, necessary manufacturing experiment; kind of a life size creative ant farm.

We had fun each and every day, but our Midwestern work ethic probably prevented us from pursuing fun for its own sake. So…“Hedonism?” …Nope; no hedonism at Hart Street. Just creative freedom.

SA: How did the US market’s difficulties in the early ‘80s affect you?

BC: Didn’t affect me at all; I was an employee whose only concerns involved making games that were fun to play. Young and oblivious to the world outside my own projects… be nice if one could maintain that innocence forever, wouldn’t it?

SA: Spy Hunter came out in 1983 and was a huge smash. What was the title like to work on? Did you have an inkling it would be such a major hit?

BC: Just prior to its release, everyone was convinced that the game was gonna be a tremendous hit. It didn’t start out that way, though. It used an experimental hybrid scrolling hardware that took a while to perfect, so it kind of flew below management’s radar for much of its development cycle… there wasn’t any real pressure to get the game out the door.

This was ideal from a design & development standpoint, since it gave the programmer, Tom Leon, the luxury of being able to tune the “feel” of the game to an exceptional level. And it gave the rest of us ample time to keep adding new gameplay features and variants to the basic game; resulting in a highly polished game with depth and substance.

SA: How involved were you in Spy Hunter’s many ports? Which machine was your favourite to work on in this period?

BC: Sorry, but I’m afraid that when it comes to questions about Ports, I can’t provide you with any real information or insights. I am typically never involved with the Port(s) to any of my games. …And because I usually managed to acquire an Arcade Cabinet of my favorite creations, I seldom played any versions other than the original(s).

SA: What do you think of Spy Hunter’s numerous reboots (in 2001, 2003 and 2012)?

BC: Again, off my radar, sorry. This is another one of those “standard questions” to which I can’t really give a well informed answer. Most folks are surprised to learn that I don’t pay too much attention to what others are doing… even if they’re doing versions of games that I helped create. Truth is… I usually spend most waking hours wrestling with the challenges of my current projects, and I only come up for air when a product ships, (2 or 3 times a year). So I am really the last person you want to ask about what’s going on in the rest of the industry.

SA: Rampage was another massive hit for you. While the influence of monster movies is easy to spot, how difficult was it to turn smashing stuff into rewarding gameplay?

BC: The gameplay was the natural result of applying the theme to work with a severely limited hardware system (i.e., “design”). We had very little to work with in terms of the number of sprites and low-resolution background blocks available, (I seem to recall that the system had enough to display 1&1/2 full screens of background images total!), but the limitations drove the creativity.

The key to the comedy was the character’s expressions, so their proportions were designed to show their faces. The efficiency of the punching & eating animation was part of the reason the core gameplay was both simple and easily understandable. The controversial (at that time) decision to feature a Join-The-Action approach that favored a Multiplayer experience for simultaneous play meant that the game needed to feature continuous little gags & surprises rather than a big, resource-heavy payoff at the end. And since Player-to-player interaction was integral to the entertainment, we had to be sure that there was no wrong way to play it!

To this day, I still firmly believe that unrestricted gameplay is the best gameplay. We effectively gave Players a sandbox full of surprises and let them go nuts.

SA: There’s very little out there like Rampage, either before or since. Were you influenced by any other games during development?

BC: Initially, yes; sort of… but not any one particular game.

The initial concept of RAMPAGE came out of a conversation about animating backgrounds that I’d seen in other games at a recent trade show. It was only after one of our tech guys said to me that our hardware couldn’t do BG animation unless we wanted to “…simply move big rectangles around…” that I instantly got the idea for Huge Buildings collapsing upon themselves! I’d already been playing with creating large, 64 pixel high (!) characters so I could better show facial expressions, and the thought of a big Player character knocking down buildings was a natural.

But other than that, “no”…

Generally speaking, if given the opportunity to do so, I try to develop games for my own amusement. If there is a game in my head that I really want to play that doesn’t exist anywhere else yet, that’s the game I want to create. Which means that I often only look at other games to make sure that what I want to do next hasn’t already been done.

SA: How did things change at Bally Midway after the Williams Electronics acquisition in 1988?

BC: The new Midway was virtually the Polar opposite to the old in many ways. To begin with, my pal, programmer Jeff Nauman and I were the only two video game designers that were asked to stay on, so it was a huge change in that respect. Everyone on the new Midway crew was friendly and welcoming, but it quickly became apparent that this environment was not the “one big happy, (if slightly dysfunctional), family” I was used to.

This new crew was around the same number of people as the old team, but this group was effectively divided into several smaller fiefdoms led by capital D Designers who were constantly competing for power, resources and control. Egos, office politics and money seemed to be the primary motivators. I never really felt comfortable at the new Midway…

SA: General Chaos was your first game as Game Refuge. How nerve-wracking was it to strike out on your own?

BC: The story actually sounds more nerve-wracking than it actually was; at the time it was just the next great adventure.

I had been contacted several times by an Electronics Arts producer who was trying to get me to move out to California and come work for EA, but I was reluctant to pull up stakes. Then one day he suddenly switched tactics and made me an offer I couldn’t refuse: he hinted that if I would form my own company, EA would produce any game my new company wanted to do, sight unseen! I had been talking to Jeff about forming an independent game development company ever since the Bally/Sente upheaval a couple of years before, and although Jeff had previously been hesitant, I was eventually able to convince him to take this leap of faith with me.

Why a “leap of faith?” Well, since we were contract employees at Midway, we couldn’t actually discuss any details with EA until after we left Midway. So we said our goodbyes, and struck out for California with nothing but a verbal promise to hang on to.

We arrived at EA, pitched our concept of a Squad-Based Multiplayer Military Game to a roomful of strangers and, except for a uncomfortable moment when one executive tried to persuade us to change the theme to a Gang War, (we said no), the project was green lit and Game Refuge Inc. became a reality.

The game was, of course, GENERAL CHAOS, which went on to become EA’s second best selling original title the year it was released.

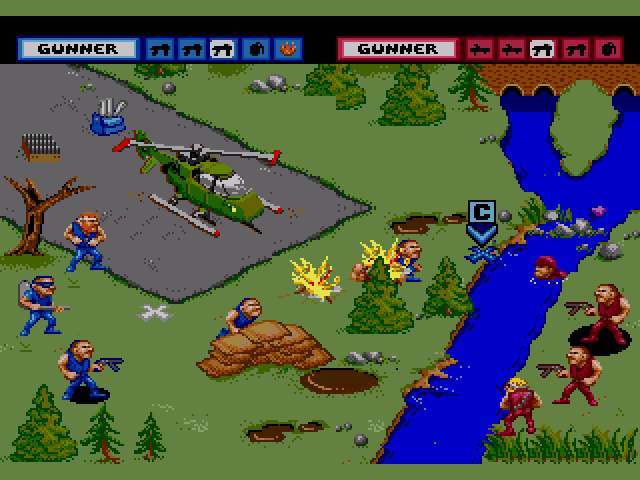

SA: General Chaos plays like a mixture of Dune II and Commando, with squad based gameplay and local multiplayer on top. How did you come up with this combination?

BC: …If you say so; I’m not actually familiar with either of those titles…

For those familiar with my early work, however, it’s apparent that I’ve always liked the idea of letting a player control multiple characters. Check out my personal game history and you’ll discover that General Chaos is just a natural extension of my previous multi-character, multi-player games. Games like ANT RAID, a battle-game in which cartoon ants fought for control of the City Dump… or SARGE, that let players control multiple combat vehicles… or ARCH RIVALS, that let players control both team members in an extremely physical two-on-two basketball contest… or PIGSKIN 621 AD, that let players control a six-man sword-wielding rugby team.

General Chaos was just another visit to my inner child’s sandbox, only this time, I was playing with army men.

SA: Was General Chaos a smooth development? Are there any things, in retrospect, you feel could have been improved?

BC: Yes, overall… the game was pretty tightly designed from the onset, so the implementation went smoothly. The addition/introduction of the 4-Player Control part-way through the process was a surprise; it would have been nice to have been able to plan for it from the beginning to take better advantage of it. But players seemed to like the options we offered, so that was cool…

SA: The character designs are vibrant, strong and instantly identifiable as General Chaos. What were your influences? Did your background in animation come into play?

BC: Thank you. I took great pride in the amount of expression & character I was able to squeeze out of the graphic limitations of the day, and I had a lot of fun doing it.

Yes, I like to think that my understanding of classic cel animation enhanced the movement. To this day, I insist that all of my 3D animators have a good understanding of the “rules” of 2D animation… you can learn a lot from Looney Tunes.

SA: What’s your personal favourite feature of General Chaos? What about your preferred character (I would argue the flamethrower is the connoisseur’s choice)?

BC: The overall gameplay mechanic of choosing a Grunt and ordering him to go ‘here’ or ‘here’ is probably my favorite feature, even with the somewhat clumsy control limitations of the Genesis D-pad.

The Gunner was my go-to guy. He didn’t have the funniest surprises or the flashiest animations, but he got the job done more often than not. (…perhaps because the opponent was busy worrying about the Scorcher?)

SA: How did game development differ in the 1990s from the 1980s?

BC: Well, the biggest change was that I went from being an employee of a large company to the owner of his own company. So, from a development standpoint, this meant that I now had to adapt all game considerations to each new Client’s expectations…which is not necessarily a bad thing; just different. You can’t do a game about a heroic radioactive bunny rabbit if the Client’s paying you to do a game based on a tragic dyslectic sheepdog.

When you’re working as an independent developer, you quickly realize that each Client comes with a unique perspective or set of criteria that you have to deal with. This Client makes casino games, this Client wants a game that features a particular product line, this Client is targeting a particular audience, this Client has a License arrangement, this Client has a proprietary platform, this Client has a severely limited timeframe or budget or window of opportunity or…

So I had to learn to apply my creative-problem-solving skills towards aspects of the process that I never really had to consider before. …Different, but still fun to solve.

I probably should explain at this point that I take a fairly simple approach to the business side of professional game development. We pretty much only do Client-funded projects. Companies interested in hiring us will approach us with prospective projects, and if the project seems to be a good fit, we take it on.

So: less creative freedom in certain respects, but a wider variety of design challenges.

SA: The Star Trek license is one of the higher profile licenses in games. What was it like working on such a big title?

BC: This one was a lot of fun, though plagued with difficulties arising from 3rd party issues outside of our control. We effectively had to develop this arcade game without the target hardware, which is not a particularly efficient way to produce a game. (Our game was finished almost a year before the game’s hardware was finished, so it effectively sat idle for a year before it was released.)

We were given a surprising amount of latitude for a licensed IP. Paramount let us write the story, create our own bosses and invent entirely new character classes. We experienced none of the horror stories involving repeated submissions or a fact-checker’s obsession with minutia that I’d heard were the norm when doing a high profile license. Instead, we had a couple of enjoyable Studio field trips, the Trekkies in the office (of which there were many) were all on cloud nine for months on end, and it was a lot of fun weaving the multiple interconnecting narrative “paths” that let the story unfold differently every time.

SA: How much ‘Voyager’ did you have to watch in preparation for the game?

BC: Well, lets see… I probably shouldn’t admit this but, “none”. The aforementioned office Trekkies were all pretty hard core, and I was more than happy to rely on their obsession & expertise.

SA: Why did you decide to go for a rail shooter? Which light gun games influenced you?

BC: Not our call. This particular Client came to us with two specifications; he had acquired the Star Trek Voyager license and he wanted a Gun Game that was “…like Area 51.” Our game used real time 3D characters over pre-rendered video, like most early rail games, but we went crazy with alternate storylines, both player-directed and hidden.

SA: Have you thought to return to light gun games given the genre’s renaissance on the Wii?

BC: We were kicking around a very cool spell-casting game for a while, but the Client’s funding fell though. Next time someone approaches us and asks us to do one, we’ll give it some serious thought yet again. (See my simple approach to the business side of things, above)

SA: A large number of your titles were developed in the arcade. What are the particular challenges of targeting the arcade compared to the home space?

BC: Arcade development means you have to design for two different groups with two opposing agendas…

1) The Player, who wants to live forever, and…

2) The Operator, who wants the player off the game as soon as possible.

Balancing both their needs sound impossible, but it’s exactly the kind of creative challenge that I find irresistible.

SA: You have a track record in creating new intellectual properties, what prompted you to return to General Chaos?

BC: First of all, I think of this as a reinvention, not a sequel or a re-skinned rehash. We’re basically starting from scratch with the original concept and an arsenal of 20 years worth of technological advancements. Although I’ve created a number of fairly popular games over the years, (Rampage, Xenophobe, Arch Rivals, Pigskin, etc), Chaos Fans continue to be the most vocal. I get more requests for a sequel /remake from General Chaos fans than any of my others. Plus, there’s never been another game that has attempted to build on the kind of frenzied real-time squad-based gameplay we introduced in the original; so the genre, (if I can call it that) is still wide open.

Personally, I’ve always felt that there was so much more we could do with the game, and with Touchscreen controls finally becoming a universal part of gaming technology, the timing seems right. Mostly though, I really, really want to play the version of Chaos that’s currently nowhere else except in my head, and I can’t do that till I make it.

SA: What advantages does running a Kickstarter give you as a game designer?

BC: Well, this is our first attempt at a Kickstarter campaign, so I’m not really sure, but the theory is: “Creative Freedom”.

Our thinking is that Kickstarter could be the means by which our Players would effectively become our Client. That way we would be developing the game for, and with, the people who will be enjoying the game when we’re done with it.

SA: In what ways will the new General Chaos build on the older title?

BC: Louder. Funnier. Easier to control. More Character classes; more weapon types. I’ve got pages of details here at the office, but there’s way too much to go into here… There’s a slightly more concise version of the whole thing on our Kickstarter page.

SA: General Chaos was at once cut-throat and comedic, is it difficult to maintain this balance in developing a new title?

BC: Not at all, my sense of humor is still my sense of humor, and the list of hysterical surprises that we’ve been dreaming up over the years could fill dozens of pages. Laughter is the key. The humor and the violence compliment each other. The cartoon look reminds the player that the action, however brutal or over-the-top, is still just a slapstick parody of that can be enjoyed guilt-free.

SA: How far into development are you? What’s the feedback been like so far?

BC: We’ve got a couple of projects that are keeping us pretty busy at the moment, so we haven’t “officially” started on the project yet; although the preliminary design work has been done for quite some time now. Nonetheless, several of us have been working on it in our spare time, lunch hours, evenings and weekends… and the excitement and enthusiasm is incredible around here right now. Everyone is chomping at the bit in anticipation.

SA: Am I free to pitch you a new character called Major Trauma?

BC: Love it! Now you have to go to our Kickstarter page and sign up for “Designers Honors.” You can write the Major’s backstory, define his weapons & upgrades, and your name will appear in the game’s design credits as a designer, right under mine.

I’m not kidding. We genuinely want to involve backers in this Game’s entire development, so we created the Designer’s Honors pledge reward to give players a unique opportunity to work with a professional team from start to finish.

Anyone who’s ever wondered what it would be like to help create a laugh-out-loud game full of ridiculous situations and bad puns… check out this Kickstarter. Less than one week left.

SA: As someone who’s seen it all, from Atari to iPhone, where do you see gaming going in the next ten years?

BC: I predicted BETA over VHS, I predicted that Cable television would fail because no one would be crazy enough to pay for TV; I predicted that the Internet was a fad. I no longer make predictions, sorry.

SA: Which games did you design but didn’t quite make it to release? What were the best ideas and why did they come up short?

BC: Like it or not, if a game doesn’t go the distance, it probably deserved to fail. I’ve had a few over the years, and a couple of them are major embarrassments.

Consider, for example, P’tooie Louie (Never released)

The player is a fur-bikini-clad boomerang-throwing cavewoman riding atop a giant red watermelon-seed-spitting pterodactyl who would periodically launch into the air to do battle with oversized, often invisible (!) killer bees! ‘Nuff said?

However, on the “good idea but never released through no fault of its own” side of the ledger, I once created a revolutionary new kind of legal casino gaming device that was licensed by a well-known international casino group who intended to replace all of their current devices in all of their casinos with this game. The rights were acquired, the casino was getting all of its manufacturing ducks in a row, the future looked rosy and… 9/11 happened. Most people don’t remember this, but VEGAS was hit hard. The project was back-burnered for three subsequent years, and eventually abandoned.

Anyone out there interested in a revolutionary new casino game?

SA: Are there any titles made by other companies which you would have liked to work on?

BC: A lot of tremendous titles out there that I love and admire, but part of what I love about them is the choices that their designers made…

So, “No’ …ultimately nothing I wish I’d worked on. Too many unrealized concepts of my own, I guess.

SA: Having developed so many games in the 1980s and on arcade hardware, how do you feel about emulation of your work? Do you draw a distinction between emulation of home hardware and arcade machines?

BC: Emulators are great for games that had simple controls. But since some of the coolest things about the arcade experience was the unique control configurations, some of my favorite games can only be enjoyed and appreciated in the arcade.

Two of my early arcade titles, Discs of Tron and Zwackery, for example, used a right handed four-way Gorf handle joystick with a Trigger and Thumb Button, and a left handed spring-loaded 360-degree spinning knob that could be raised or lowered to achieve multiple effects.

Try emulating that on a keyboard.

SA: Finally, which is your greatest accolade: Spy Hunter being featured in ‘Murder, She Wrote’, being inducted into the White Castle Hall of Fame, or Rampage World Tour being played in the Leonardo Di Caprio film ‘The Beach’?

BC: LOL

You forgot the very short lived Cartoon show that featured Tyrone from ARCH RIVALS, and the upcoming RAMPAGE live action CG movie…

But seriously, it sounds corny, but the best part of my job is seeing the smiles on players’ faces. Nothing beats that.

Brian Colin, thank you for your time.

With FaceBook you can keep up to date with Game Refuge and General Chaos II‘s development. Don’t forget to visit and support the project at the Kickstarter page.